Effect and the Near Inexpressible Majesty of Layers

Effect and the Near Inexpressible Majesty of Layers

The precise reasons for my transfixion upon Effect's Layer type are difficult to compress. Now, I could flail pedagogically toward some vague zenith shouting "testability," "beauty," "dependency injection," or even "fractality!" and yet, for all my perspiring, you'd still calmly inform me that this is, has always been, and shall remain ever after an Arby's, whilst covertly spamming the silent sub-counter alarm that occasions my arrest.

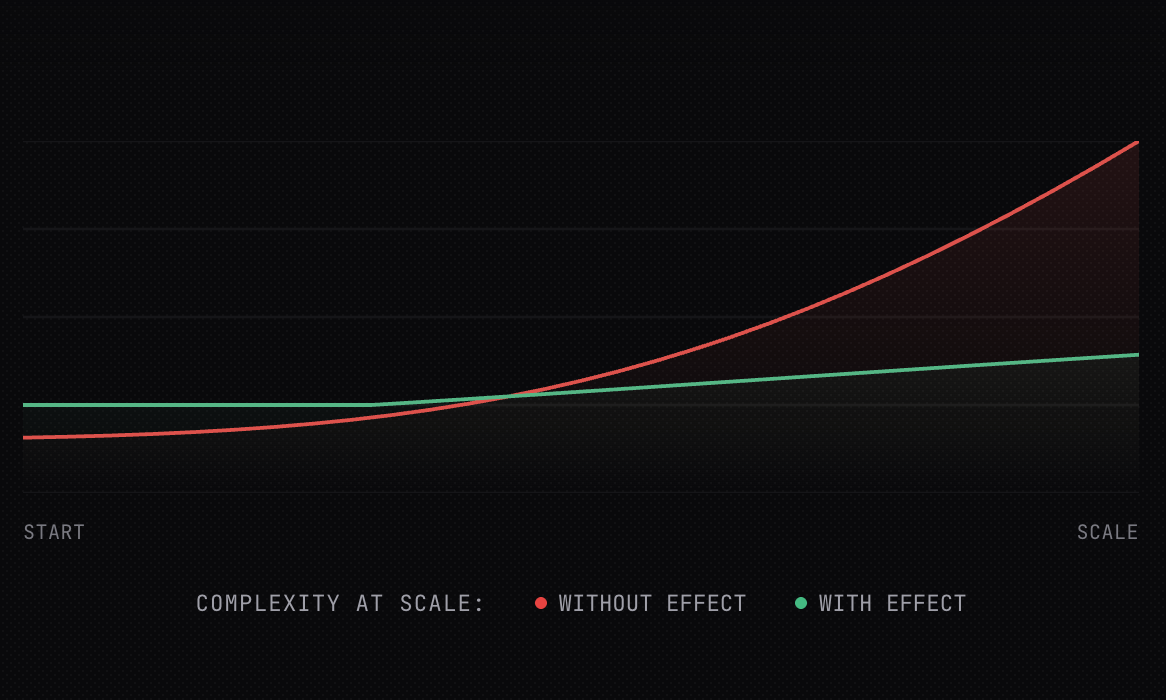

This incompressibility is an unfortunate aspect of all Effect curricula. This graph, prominently featured on the library's website, does a fine job of illustrating my conundrum.

A certain number of concepts must first be unfurled at the prospective user's feet, and reckoned with individually, before they're able to comprehend the surprising power compacted into their gestalt — this explains the characteristic months-long incubation period between initial exposure and full-bore Effect evangelism. My usual tactic is to plead for a suspension of disbelief, to ask that they trust me as they would their own Effect-pilled grandmother, and then swiftly clap on the floodlights and turn a terrible mirror upon them!

The average TypeScript practitioner has habituated itself to a degree of suffering and uncertainty that becomes retrospectively sadomasochistic once it has sufficiently glimpsed the effectful alternative. The initial chapter of Effect Institute attempts to gently expose the listener, in their vulnerable, semi-ASMR-tenderized condition, to their many unwitting self-flagellations.

In this vein — though textually, as I'm presently traveling by aeroplane — let's countenance, most fluorescently and unflatteringly, the current state of defining and testing services in JavaScript.

Without Effect

Imagine the following scenario:

You're a prompt engineer at a respectable online pharmaceutical startup. One day, Claude, to whom you've long since handed unilateral control over your home automation system, suddenly begins strobing your lights whilst blasting that part of Bill Withers's "Lovely Day" where he just goes "daaaaaaaaayyyyyyyy" interminably out of every possible sound-emitting orifice in your tenement. You know well by now that there's a freshly minted Jira ticket with your name on it.

You slump off your modular sleeping platform and heave it back into its recess, simultaneously causing a desktop to extrude from the opposite wall of your tiny, squalid, loud, flashing room. You groggily survey the in-desk readout to discover that your manager's Claude has selected you as the federally mandated Human-in-the-Loop for a new "surge pricing" feature (As a customer with a rare and luxurious disease, I want pricing to vary with demand such that my medication is safeguarded from the underemployed). You ssh into a very distant place.

Claude's Code

In a matter of milliseconds, you're connected, and a commit is already waiting for you.

You begin your review.

commit 9f8e7d6c5b4a3

Author: Claude <claude@anthropic.com>

Date: Mon Jan 27 04:32:00 2031 -0500

feat(pricing): implement surge pricing for high-demand medications [PHARM-5485]

Approved-By-HITL: MISSINGYour Claude has added a new feature-flags.ts file. This exports an isEnabled function that simply fetches the given feature flag's state from an approved vendor. So far, so good.

// feature-flags.ts

export const isEnabled = async (flag: string): Promise<boolean> => {

const res = await fetch(`https://api.flags.com/flags/${flag}`, {

headers: { Authorization: process.env.FLAGS_API_KEY! }

})

const data = await res.json()

return data.enabled

}You press your thumb into a concavity near the right edge of the slab-screen. There's a pinch as a dram of blood is extracted, whereupon the still-blaring "-aaaaaaaaaayyyyy" dips to a marginally less deafening volume.

"Hunk one complete. Twenty-four hunks remaining."

Next up, the pricing module uses isEnabled to determine whether or not surge pricing should be applied and, if so, applies a modest markup.

// pricing.ts

import { isEnabled } from "./feature-flags"

export const getPrice = async (basePrice: number): Promise<number> => {

if (await isEnabled("surge-pricing")) {

return basePrice * 6.5 // 550% markup

}

return basePrice

}You automatically offer your thumb to the concavity. A second driblet of blood is drawn out of you and into the hemobiometrical machine.

"Hunk two complete. Twenty-three hunks remaining."

The next hunk reveals a test file. You lean in, curious how Claude intends to probe a function with a network dependency. A cursory glance across the buffer tightens your throat and wicks the moisture from your tongue. There is mocking afoot.

// pricing.test.ts

import { vi, describe, it, expect } from "vitest"

vi.mock("./feature-flags", () => ({ isEnabled: vi.fn() }))

import { isEnabled } from "./feature-flags"

import { getPrice } from "./pricing"

describe("getPrice", () => {

it("applies surge pricing when enabled", async () => {

vi.mocked(isEnabled).mockResolvedValue(true)

expect(await getPrice(100)).toBe(650)

})

it("returns base price when surge pricing is disabled", async () => {

vi.mocked(isEnabled).mockResolvedValue(false)

expect(await getPrice(100)).toBe(100)

})

})Claude has ingested this pattern countless times throughout his debauched pre-training data bender. Yet prevalence should not be mistaken for soundness. As the man himself might put it: this isn't just a footgun — it's a foot armada! You're absolutely fucked.

And how is it that you are, in this regard, fucked? Let us enumerate.

Beyond the perverted mechanisms by which these mocking libraries operate, they're inherently limited, especially with regard to type-safety. For instance, what if you misspell the file name? What if you rename the file in the future, and forget to update the call to mock? Well, nothing would happen; the mock would miss its target and you'd be none the wiser.

vi.mock("./future-flaps", () => ({ isEnabled: vi.fn() }))What if you fat-finger the function name? Then you'd be mocking an imaginary isEnable function, while isEnabled runs for real in your tests.

vi.mock("./feature-flags", () => ({ isEnable: vi.fn() }))What if your mock returns the wrong type? The mocking API is entirely untethered from the type system. If you return a string where a boolean is expected, it'll type-check all the same.

vi.mocked(isEnabled).mockResolvedValue("sure")Further, the signature of getPrice gives no indication whatsoever of its dependence upon feature flags. Nothing at the type-level apprises us of this relationship.

export const getPrice = async (basePrice: number): Promise<number> // ???Wait, do I hear a scoff? Is that the telltale clink of a monocle hitting your teacup? Do you mutter into the mahogany cuff of your caviar sport coat, "Blasphemy! This is not the domain of a type checker. Types are trifling, decorative things like Shetland ponies and ceramic frogs, to be placed about the codebase for our amusement!"

I disagree, my friend. Especially in this age of the agent managerial class, types force both ourselves and our ephemeral, jaggedly-doltish factotums to deal with reality as it stands. They let us validate the fundamental cohesion of our programs long before they run amok in production. They're a form of documentation that cannot drift, as they are themselves the very source of truth worth documenting. In our feature flag scenario, a Claude couldn't know these implicit, inter-module dependencies without first reading each and every file in full, clogging its precious, small context with mostly irrelevant junk.

Try to hold in your mind these many inadequacies as we consider the effectful model.

With Effect

Effect affords a beautifully regular and self-similar architecture. Its approach to dependency injection, in particular, makes testing even the most complicated async code nearly trivial.

There is, of course, the aforementioned obstacle of syntactic and conceptual overload (if you know nothing of Effect, I'd recommend working through the first two chapters of my little Institute). By the end of this, you should fully understand Context.Tag, Layer, and our definition of service.

Defining a Service

Think of Context.Tag as an effectful interface. Here, we define a FeatureFlags service, composed of a type, a string "tag", and the shape of the interface it represents.

In plain TypeScript, you might write:

interface FeatureFlags {

readonly isEnabled: (flag: string) => Promise<boolean>

}The Effect equivalent:

class FeatureFlags extends Context.Tag("FeatureFlags")<FeatureFlags, {

readonly isEnabled: (flag: string) => Effect.Effect<boolean>

}>() {}Behold, our abstract service definition, sans implementation. I admit there is some unpleasant syntactic overgrowth (e.g., FeatureFlags in triplicate). Alas, for the behavior we desire, this is unavoidable in TypeScript, our otherwise most gracious host language. If you could forestall your recoiling until you've seen the full picture, I don't believe you'll regret it.

Implementing a Service

Think of a Layer as an effectful constructor for our service. Here we define a test implementation of FeatureFlags, parameterized by its enabled flag names.

const featureFlagsTestLayer = (...enabled: string[]): Layer.Layer<FeatureFlags> =>

Layer.succeed(FeatureFlags, {

isEnabled: (flag) => Effect.succeed(enabled.includes(flag))

})Our layer is defined as a function so that we can provide different sets of flags on a per-test basis. Layer.succeed is used because we're directly providing a concrete implementation (this mirrors Effect.succeed). We must pass our FeatureFlags tag as the first argument for reasons we'll get into later; for now, please accept this as part of the ritual.

Defining a Second Service

Next, let's define Pricing as a service. Once more, we extend Context.Tag and specify the interface:

class Pricing extends Context.Tag("Pricing")<Pricing, {

readonly getPrice: (basePrice: number) => Effect.Effect<number>

}>() {}Most applications naturally decompose into services. This is the self-similar, fractal quality I alluded to earlier. To begin reaping the benefits of this pattern, let's implement a layer (read: an effectful constructor) for our Pricing service.

// 1. Define the layer

const pricingLayer = Layer.effect(

Pricing,

Effect.gen(function* () {

// 2. Grab hold of our transitive dependencies

const flags = yield* FeatureFlags

// 3. Close over these dependencies in our implementation

const getPrice = Effect.fn(function* (basePrice: number) {

const surging = yield* flags.isEnabled("surge-pricing")

return surging ? basePrice * 6.5 : basePrice

})

// 4. Return the implementation

return { getPrice }

})

)This time we use Layer.effect because our implementation needs to acquire another service at construction time. Inside Effect.gen, we write yield* FeatureFlags to obtain an instance of the FeatureFlags interface.

Let's look at the type of our pricingLayer:

Layer.Layer<Pricing, never, FeatureFlags>

// ^^^^^^^^ what it provides

// ^^^^^ how it can fail

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ what it requiresAs a consequence of our plucking FeatureFlags out of the air with yield*, it is tracked at the type-level. It is now impossible to run a program that uses this layer without also providing an implementation of FeatureFlags. Let's take a brief aside to see what this means in practice.

An Interlude on the Introduction and Elimination of Requirements

If this type-level tracking of requirements feels unfamiliar, consider that you already do this every day in TypeScript. A function parameter is an unsatisfied requirement, and calling a function with an argument eliminates it. All of your intuitions around function types should map cleanly onto Effects and Layers.

Just as a function's parameters signify its requirements, an Effect's third type parameter serves the same purpose.

const useConfigFunction: (config: Config) => string = ...

// ^^^^^^ ^^^^^^

// requires returns

const useConfigEffect: Effect<string, never, Config> = ...

// ^^^^^^ ^^^^^^

// returns requiresCalling a function with an argument eliminates the requirement; providing a Layer does the same for an Effect.

const config: Config = ...

const result: string = useConfigFunction(config)

// ^^^^^^

// fully satisfied

const configLayer: Layer.Layer<Config> = ...

const effect: Effect<string, never, never> = useConfigEffect.pipe(Effect.provide(configLayer))

// ^^^^^

// fully satisfiedOne difference worth noting is that calling a function executes it immediately, whereas Effect.provide merely satisfies the requirement without running anything. The more honest functional analog would be closing over the argument in a thunk, which would likewise remain inert until explicitly invoked:

const thunk: () => string = () => useConfigFunction(config)

const effect: Effect<string> = useConfigEffect.pipe(Effect.provide(configLayer))Let's put this all together. First, we'll define a simple Random service by extending Context.Tag to specify our interface:

class Random extends Context.Tag("Random")<Random, {

readonly nextNumber: Effect.Effect<number>

}>() {}Next, we give it an implementation. Actually, let's give it two: a real one that delegates to Math.random, and a fixed one for testing that always returns whatever number you give it.

const randomLayer = Layer.succeed(Random, {

nextNumber: Effect.sync(() => Math.random())

})

const fixedRandomLayer = (n: number) => Layer.succeed(Random, {

nextNumber: Effect.succeed(n)

})Finally, we define a program that uses the Random service:

const coinFlip: Effect.Effect<string, never, Random> =

Effect.gen(function* () {

const random = yield* Random

const n = yield* random.nextNumber

return n > 0.5 ? "heads" : "tails"

})Our type, as expected, indicates that coinFlip requires Random. If we naively attempt to run it without providing that dependency, the compiler protests.

Effect.runPromise(coinFlip)

// Type Error: Missing 'Random' in the expected Effect context.To satisfy the requirement, we use Effect.provide and pass in our Math.random-backed implementation.

const effect = coinFlip.pipe(Effect.provide(randomLayer))

// effect: Effect<string, never, never>

// ^^^^^ ready to run!Now that we have provided all of our dependencies, we can run it.

Effect.runPromise(effect).then(console.log)

// => "heads" or "tails"Or, if we want deterministic behavior for testing, we provide the fixed layer instead:

const testable = coinFlip.pipe(Effect.provide(fixedRandomLayer(1)))

Effect.runPromise(testable).then(console.log)

// => "heads" (always, since 1 > 0.5)And to complete our tangent, we should cover what happens when a layer for a service depends upon another service, just like our pricingLayer depends on FeatureFlags.

We could, just for fun, define an implementation of Random that asks the user to input a number via a terminal prompt. Let's implement this with Effect's Terminal service:

import { Terminal } from "@effect/platform"

const terminalRandomLayer = Layer.effect(

Random,

Effect.gen(function* () {

const terminal = yield* Terminal.Terminal

const nextNumber = Effect.gen(function* () {

yield* terminal.display("Enter a number: ")

const input = yield* terminal.readLine

const n = parseFloat(input)

if (isNaN(n)) {

return yield* Effect.fail("Invalid number")

}

return n

}).pipe(Effect.eventually) // keep asking until valid

return { nextNumber }

})

)

// terminalRandomLayer: Layer.Layer<Random, never, Terminal.Terminal>

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

// depends on Terminal!Because we yield* Terminal.Terminal inside the layer, our terminalRandomLayer now requires Terminal, which is reflected at the type-level. To use it, we must provide a Terminal implementation to our terminalRandomLayer.

import { NodeTerminal } from "@effect/platform-node"

const appLayer: Layer.Layer<Random> = terminalRandomLayer.pipe(

Layer.provide(NodeTerminal.layer)

)And then we can provide this composed layer to our coinFlip program:

const program = coinFlip.pipe(

Effect.replicateEffect(3),

Effect.provide(appLayer)

)Running this program prompts us three times and returns an array of results:

$ bun main.ts

Enter a number: 0.8

Enter a number: 0.2

Enter a number: 0.6

[ "heads", "tails", "heads" ]

The Payoff: Testing

With that out of the way, let's return to testing our pharmaceutical surge pricing feature.

Recall that pricingLayer depends on FeatureFlags. So, to test Pricing in isolation, we'll start by defining a helper function that returns a fully satisfied Layer.Layer<Pricing> by providing our in-memory FeatureFlags implementation to our pricingLayer:

const testLayer = (...enabled: string[]): Layer.Layer<Pricing> =>

pricingLayer.pipe(Layer.provide(featureFlagsTestLayer(...enabled)))This will let us vary the enabled feature flags per test. Now, to actually write the tests, we'll make use of the @effect/vitest module.

describe("getPrice", () => {

it.effect("applies surge pricing when enabled", () =>

Effect.gen(function* () {

const pricing = yield* Pricing

const price = yield* pricing.getPrice(100)

expect(price).toBe(650)

}).pipe(Effect.provide(testLayer("surge-pricing")))

)

it.effect("returns base price when disabled", () =>

Effect.gen(function* () {

const pricing = yield* Pricing

const price = yield* pricing.getPrice(100)

expect(price).toBe(100)

}).pipe(Effect.provide(testLayer()))

)

})Here we yield* Pricing and use the returned service to get the price. In the first test, we check that surge pricing applies a hefty markup. In the second, we verify the base price is returned when the flag is disabled.

All of our tests pass, and everything is type-safe:

✓ pricing.test.ts (2 tests) 4ms

✓ getPrice > applies surge pricing when enabled

✓ getPrice > returns base price when disabledWe cannot forget to provide an implementation of FeatureFlags, and we cannot misspell a service or a function because we're relying on the actual services instead of some diabolical import swizzling. Furthermore, it is trivial (and fun!) to design curated test implementations of our services, rather than artlessly slapping together brittle and ad hoc mocks.

Under the Hood

Now that you're fully convinced of the supremacy of Effect and its attendant abstractions, you are free to go forth and rewrite all of your projects and sequester yourself from all effect-less nonbelievers. However, before I release you, I'm obliged to explain a bit of how this all works internally.

The Effect runtime, most famous for running Effects, implicitly provides a Context to every Effect. This Context is basically a map from string keys to any values.

// A simplified mental model

type Context = Map<string, any>When we defined FeatureFlags by extending Context.Tag("FeatureFlags"), that "FeatureFlags" string is what serves as the key in this map. Later, when we implemented our service with Layer.succeed and Layer.effect, we needed to provide a tag to these functions because a Layer is (modulo a few details) an Effect that returns a Context map.

// A very simplified implementation of Layer.succeed

const succeed = (tag, impl) => Effect.sync(() => {

// e.g., [["FeatureFlags", { isEnabled: ... }]]

return new Map([[tag.key, impl]])

})

// A very simplified implementation of Layer.effect

const effect = (tag, make) => Effect.gen(function*() {

const impl = yield* make

// e.g., [["FeatureFlags", { isEnabled: ... }]]

return new Map([[tag.key, impl]])

})Then, when we finally yield* FeatureFlags, what we're really doing is just indexing into that ambient, runtime-provided Context with our tag's key.

// A simplified mental model of yield* FeatureFlags

const context = yield* Effect.context()

const flags = context.get(FeatureFlags.key)! // => { isEnabled: ... }This might sound unsafe, but it isn't, because the whole system is correct by construction. Whenever you yield* a tag, its type propagates to the surrounding Effect's requirements. Conversely, when you provide a layer, its output's type is eliminated from the underlying Effect's requirements. Layer constructors, like Layer.succeed and Layer.effect, are constrained by the type of the provided tag, forcing the implementation to match the expected interface. If your program type-checks, every lookup is guaranteed to succeed with the correct type.

The End

There is something deeply calming, to me at least, about the regularity of it all. Much of your app can be expressed as interlocking services, with their interfaces specified with Tags and implemented with Layers. Once a handful of novel concepts are absorbed — a process which I hope to have accelerated here — you'll have a design primitive that can be composed into arbitrarily complex applications, as trees of services with explicit, transitive dependencies, all while remaining perfectly type-safe and eminently testable.

The resulting uniformity is a useful property, both for us humans and our robot friends. The question of application structure is resoundingly answered, and we're freed up to concern ourselves with more interesting and meaningful problems. Take care, and check out Effect Institute.

∎